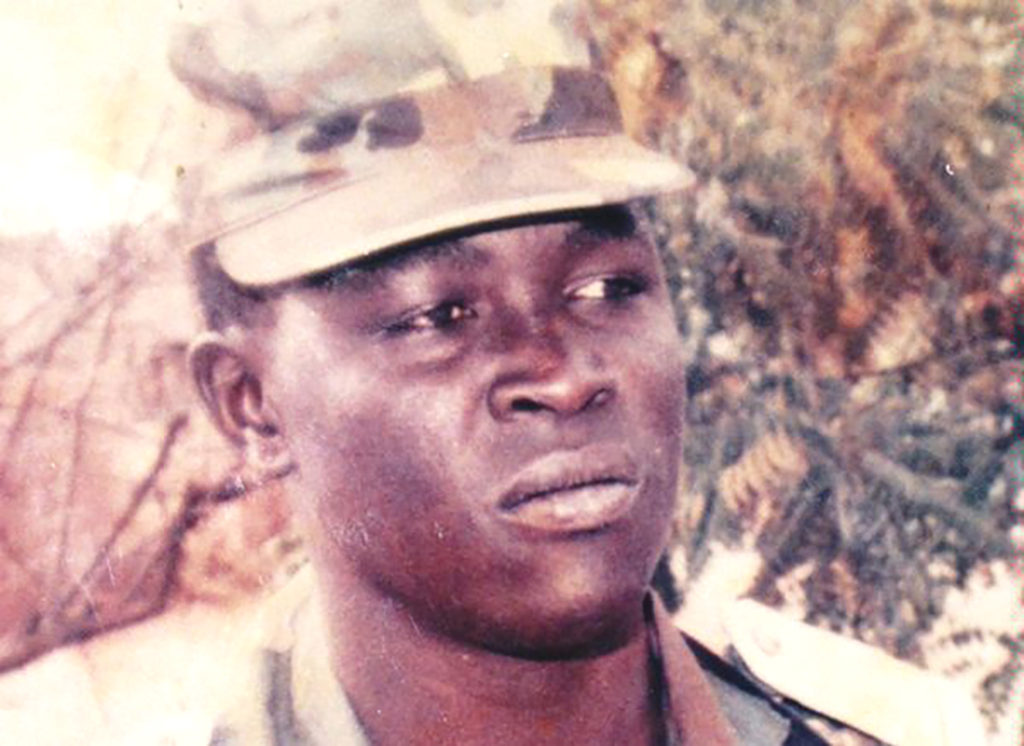

He acted from his heart

ADF STAFF

In 1994, after the assassination of the president of Rwanda, soldiers of the presidential guard tortured and killed Prime Minister Agathe Uwilingiyimana, her husband and 10 Belgian peacekeepers. Hutu extremists took power and began the infamous Rwandan genocide, killing hundreds of thousands of members of the Tutsi minority and some politically moderate Hutus.

That same morning, United Nations peacekeeper Mbaye Diagne got word of the murders. The Senegalese captain went to investigate and found the prime minister’s five children hiding. When reinforcements did not arrive, Mbaye hid the children under blankets in his vehicle and drove them to the safety of a Kigali hotel, which served as a U.N. compound.

The genocide lasted but 100 days, but as many as 1 million Rwandans were slaughtered.

Mbaye, working on his own and armed with little more than food, cigarettes and alcohol for bribes, began rescuing Rwandans from the roaming killers, hiding them in his vehicle in much the same way he had hidden the prime minister’s children. As a U.N. observer, he was always unarmed.

The United Nations had rules forbidding its observers from getting involved in rescuing civilians, but Mbaye was not one for following orders. His U.N. superiors chose to look the other way because, they conceded, Mbaye was doing an honorable and courageous thing.

He had always been a singular man. One of nine children in his family, he was the first to go to college. After graduation, he enlisted in the Senegalese Army, and in 1993 he joined a U.N. peacekeeping force in Rwanda.

Mbaye used bribery to distract guards at traffic stops, but perhaps his best tool was his gregarious personality. The devout Muslim, a big man, was funny and sarcastic and smiled constantly.

In his rescue missions, he could carry as many as five people under blankets in the back of his vehicle. He passed through dozens of checkpoints on each trip.

On one occasion, he helped organize a truck convoy to take Tutsi refugees to an airport so they could leave the country. A crowd of militiamen stopped the trucks and began trying to pull the refugees out. A doctor who was among the refugees told the BBC that Mbaye got between the trucks and the crowd.

“Capt. Mbaye ran up,” the doctor said. “And he stood between the lorry and the militiamen holding his arms out wide. He shouted, ‘You cannot kill these people; they are my responsibility. I will not allow you to harm them — you’ll have to kill me first.’ ”

Although the convoy had to turn back, Mbaye’s actions saved the passengers.

Gregory Alex, head of a U.N. humanitarian assistance team at that time, told the U.S. Public Broadcasting System that Mbaye was always on the move, looking for people to save.

“We’re talking about saving hundreds of people three or four at a time,” he said. “So you imagine when we talk about the 23 checkpoints, and you take even 200 people, you divide it by the maximum five — that would mean he [would] have five people in a vehicle, which is too conspicuous, too. So he would do it in smaller numbers, so that he wouldn’t draw so much attention to people. But he’d go through all these checkpoints, and at every checkpoint you have to explain yourself.”

He never got caught. Two weeks before his scheduled return to Senegal, he was driving to U.N. headquarters when a mortar shell landed behind his jeep. Shrapnel hit him in the back of his head, killing him. He was 36 years old.

Mbaye’s courage has not been forgotten. In 2014, the United Nations created the “Captain Mbaye Diagne Medal for Exceptional Courage” in his honor. The U.N. considered 10 people for the award before deciding the first one should go to Mbaye’s family.

On May 19, 2016, U.N. Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon presented Mbaye’s widow, Yacine Mar Diop, and their two children with the inaugural award.

“He did not turn a blind eye or a deaf ear,” Ban said at a ceremony at the U.N. “He did not ignore his conscience or walk away in fear. He acted from his heart.”

Journalist Mark Doyle described Mbaye in simple terms. The big Sengalese Soldier was, Doyle said, “the bravest man I have ever met.”