The West African Epidemic Shines a Light on the Need for Water and Sanitation Infrastructure

In late 2013, Ebola took root in West Africa, spreading like wildfire and throwing the region into chaos. By early March 2015, it had killed nearly 10,000, mostly in Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone.

As Ebola raged, a quieter, more insidious killer took its toll all over the continent: a lack of clean water. London-based nongovernmental organization WaterAid estimates that dirty water killed 73,000 — more than seven times as many people as Ebola — in Nigeria alone in 2014.

Nigeria is not unique in Africa when it comes to water and sanitation problems. Consider these incidents from just the past five years:

• Cholera spread through West and Central Africa in 2011, infecting at least 85,000 and killing nearly 2,500.

• A year later, Guinea and Sierra Leone had seen more than 14,000 cases of cholera — with up to 300 deaths — by August 2012.

• Lassa fever is spread by rats and produces symptoms similar to Ebola. It infects between 100,000 and 300,000 West Africans annually, killing an estimated 5,000.

All of these threats can be directly linked to poor sanitation practices, lack of clean water, and underdeveloped health and sanitation infrastructure. And all of them have been bedeviling the continent longer and with greater frequency than the West African Ebola crisis.

Ebola Epidemic Serves As A Wake-Up Call

A lack of clean water, the practice of open defecation, and health-care facilities decimated by years of civil war have combined with Ebola to bring attention to sanitation deficiencies. As a result, observers on and off the continent are calling for more investment and lifestyle changes to prevent and adequately address disease and health-related issues.

“Sometimes it takes an outbreak for positive things to happen. Maybe it takes Ebola for sanitation and water to become a top priority,” Bai-Mass Taal, executive secretary of the African Ministers’ Council on Water, told the Thomson Reuters Foundation. “This is like a blessing in disguise: Nobody wants it to happen, but you use it as a means to have more commitment and investment in water and sanitation.”

Calestous Juma, Kenyan-born professor of the Practice of International Development at Harvard University, said lasting solutions to the Ebola crisis will have to address poor infrastructure and a lack of investment in public health. “The Ebola outbreak is not an episode; it is a wake-up call for strategic political action,” Juma wrote for aljazeera.com.

“The limited availability of basic amenities such as clear water and sanitation adds more pressure on the stressed health services. Infrastructure and public health are intricately connected,” Juma wrote.

Sanitation is Linked to Public Safety

Cholera rides into West Africa and elsewhere during perennial rainy seasons. Areas flood — particularly densely populated urban slums — and floodwaters mix with open sewers and human waste to sicken residents by the thousands through contaminated water.

“If your area is flooded with rainwater, and if people are defecating in the open, it will get into the water supply,” Jane Bevan, a regional sanitation specialist for UNICEF, told The New York Times. “We know governments have the money for other things. I’m afraid sanitation is never given the priority it deserves.”

In November 2014, the United Nations used the occasion of “World Toilet Day” to call for an end to open defecation. A U.N. report, released to coincide with the event, notes that many in Liberia and Sierra Leone — countries hit hardest by Ebola — have virtually no toilet access.

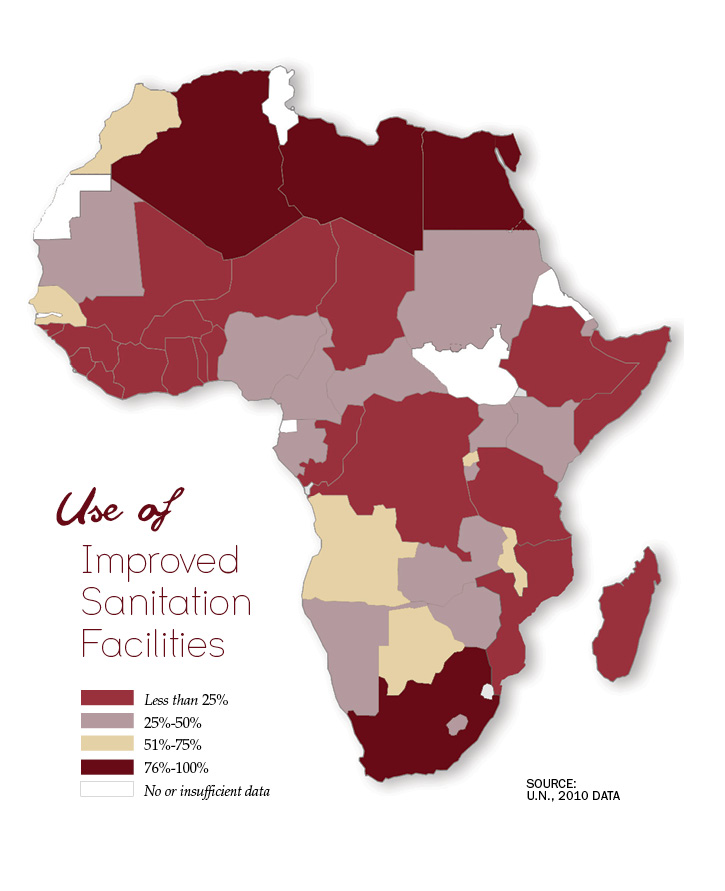

The problem is not just a challenge for Africa. Worldwide, 2.5 billion people lack adequate toilets. In Africa, the total is roughly 644 million out of more than 1 billion people — about 64 percent.

Chris Williams, executive director of the Water Supply and Sanitation Collaborative Council in Geneva, said open defecation spreads disease, hurts economic productivity and leads to unnecessary deaths. “People who do not have access to a hygienic toilet and a place to wash their hands are exposed to an array of fecally transmissible and potentially deadly diseases that with improved sanitation are easily preventable,” Williams told IPS in May 2014.

In the countries affected by the recent Ebola outbreak, 25 to 40 percent of the population lacks clean water, according to the World Health Organization. Sometimes, even Ebola treatment centers have no running water. Dr. David L. Heymann, professor of infectious disease epidemiology at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, told ADF that lack of proper sanitation practices and infection control in hospitals have been problems in past and current Ebola outbreaks.

Open defecation and the lack of sewer infrastructure have not been identified as causes of Ebola or linked to its transmission. However, direct contact with body fluids and human waste are documented modes of transmission and can amplify outbreaks. Ebola doesn’t appear to be passed through contaminated drinking water, Heymann said. But he adds that this is the first major outbreak of the disease, so there are questions about it that can’t be answered yet.

What is clear, Heymann said, is that fecal contamination can spread diseases such as polio and cholera through tainted drinking water or through direct contact with sewage and human waste. Diarrhea also is common in Africa and has killed far more people than Ebola.

In 2013 alone, 47 countries worldwide reported 129,064 cases of cholera to WHO. Of those, 43 percent — more than 55,000 — were reported in Africa. But the global total is known to be much higher: WHO says an estimated 1.4 million to 4.3 million cases occur each year, and death totals range from 28,000 to 142,000 annually.

Solutions Can Include NGOs, Militaries and Companies

WaterAid has worked to improve access to clean water and adequate sanitation all over the world. In budget year 2013-14, the organization made clean water available to 885,000 Africans, and it provided improved sanitation and toilet facilities to nearly 1.5 million on the continent.

The agency worked with local governments and communities in Sierra Leone to rebuild water and sanitation services devastated after a decade of civil war. Fighting left many wells and toilets destroyed. Nearly half of Sierra Leone’s more than 5.7 million people were forced out of their homes as fighting continued, leaving them without adequate sanitation and water. WaterAid tells of Hawa Turay, who upon returning to her village of Vaama, collected water from a river contaminated with waste from a nearby hospital. Cholera killed three of her children. WaterAid worked with local partners to repair broken infrastructure. Now, a trained committee of residents in Vaama maintain water and sanitation infrastructure.

WaterAid also provides education to go along with services. “When I went for training, I was taught about sanitation, and when I finished my course, I went out into the villages,” said Francesca Banji, a hygiene facilitator in Zambia. “I went to each village and visited people’s houses so that I trained them to train others.”

In Senegal, the military has taken a prominent role in providing infrastructure of all kinds, including sanitation services. The military’s Armée-Nation program has been a model of civil-military cooperation for years and has contributed to stability and good will. Among the military’s many public works projects are construction of waste treatment facilities, wells, and lakes and water retention basins. Soldiers also revitalize and clean public spaces.

According to 2012 estimates, 67 percent of Senegal’s urban population and nearly 41 percent of rural dwellers had access to improved sanitation facilities. That works out to about 52 percent of the total population, according to The World Factbook, more than any of the three nations most affected by Ebola in 2014. In Ghana, the Armed Forces’ 48 Engineer Regiment also builds public works projects.

Militaries usually have the personnel, equipment and expertise to perform a wide range of construction and service projects. But Soldiers must be seen as allies by civilians who need services.

The Problem of Priorities

Infrastructure of any kind takes money. Just as important as money is the political will to make health and sanitation a national priority. That has not always been the case in Africa, said Dr. Earl Conteh-Morgan, a native Sierra Leonean and professor of international studies at the University of South Florida. Development often seems to come in the form of “conspicuous industrialization,” he said.

“I think the African governments probably think that development is only when you have a big stadium, a nice city council center, and maybe concentrate a lot of the money at the universities,” Conteh-Morgan said. “And they forget, in fact, that a water system, a clean water system, is really, really necessary.”

“I believe they have a problem of priorities,” he said. “They do not prioritize something like good health care.”

Dr. Offei “Bob” Manteaw, director of research, innovation and development at Zoomlion Ghana Ltd., agrees. The company specializes in a wide range of waste-handling services, from janitorial work to landfill management. He said the challenge for Ghana and many other African nations, especially regarding sanitation infrastructure, is a lack of planning and political will.

“If there was a prioritization, if there was a realization of the importance of public health and all other health issues to national development, then it doesn’t matter the size of our purse, we will dedicate some to taking care of some of these basic things,” Manteaw told ADF.

Zoomlion builds mobile toilet facilities and has worked with the government to place them in slums and densely populated areas. He said his company and others could provide more of these services, but government support is crucial. The company also does business in Angola, Equatorial Guinea, Liberia, Togo and Zambia.

Manteaw also is involved with the Africa Institute of Sanitation & Waste Management, which opened in Accra in November 2013. The institute, which is affiliated with the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, trains individuals and companies from all over the continent on waste management through undergraduate and graduate programs.

“We’re hoping that through such engagement and exchanges we will develop and share knowledge that could be replicated and adapted to specific cultures and contexts across Africa to help solve the sanitation challenge that most of African cities face,” he said.

“We’re hoping that through such engagement and exchanges we will develop and share knowledge that could be replicated and adapted to specific cultures and contexts across Africa to help solve the sanitation challenge that most of African cities face,” he said.

Manteaw has seen opportunities emerge since Ebola prompted calls for better sanitation. First, he pitched a subregional “post-Ebola cleanup” to the Economic Community of West African States. There has been some communication back and forth, and he hopes to keep the idea alive. Second, he said nations should look for ways to “add value” to waste so there would be some incentive for citizens to keep areas clean. As an example, he used plastic water bottles, a pervasive sight in Ghana and elsewhere. He envisions sanitation parks where people could bring water bottles and sell them to facilities that would crush them and reuse them to make other things, such as waste bins. “If we can formalize it, bring some organization around it, it will solve the problem on the streets.

“A post-Ebola cleanup should not just be collecting waste from somewhere and going to dump it,” Manteaw said. “Let’s change the culture of waste management in the subregion.”