Bringing Peace to Africa’s ‘Arc of Instability’ Will Require Action in the Security Sector and the Halls of Government

ADF STAFF

The 7,000-kilometer cross-continental journey that begins in the Horn of Africa and stretches across the Sahel into West Africa will pass through numerous conflict areas. The band of territory is rife with poverty, illicit trafficking, war, terrorism and ethnic unrest. The path shares common characteristics that have led it to be known by some as the “arc of instability.”

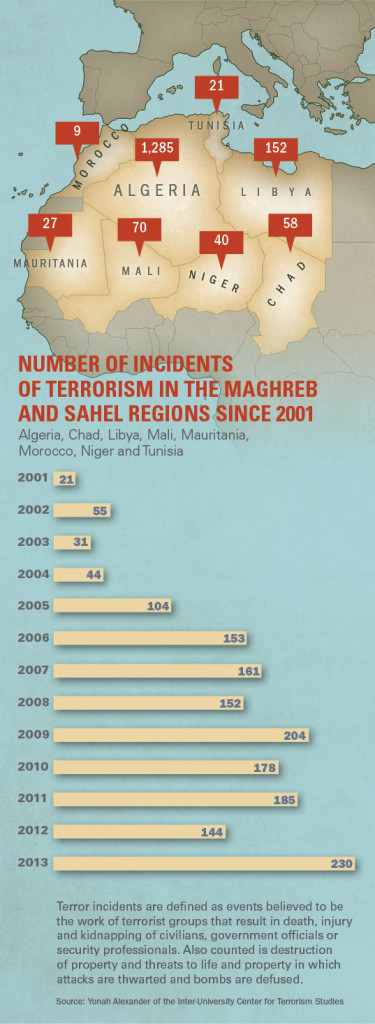

In Somalia, al-Shabaab militants capitalized on years of lawlessness to dole out murder at home and beyond. Rebel groups hold sway in parts of South Sudan and, farther north, factions continue to clash in Darfur. In Libya, weapons flow across the border into neighboring countries. In Mali, a complicated stew of ethnic and ideological groups has thrown that nation’s north into chaos.

The arc of instability is an attempt to characterize a diverse group of countries that may share little more than climate and vast open, often ungoverned, spaces. Language, culture and religion often differ, sometimes within a single nation. If left unchecked, the arc “could transform the continent into a breeding ground for extremists and a launch pad for larger-scale terrorist attacks around the world,” the United Nations Security Council was told in May 2013.

ORIGINS OF THE ARC

Something as amorphous as the arc of instability is difficult to describe and even harder to remedy. Its origins are equally complicated. Nations along the arc typically share some general characteristics:

An arid and harsh climate. According to a United Nations Environment Programme report, the Sahel has been called “ ‘ground zero’ for climate change due to its extreme climatic conditions and highly vulnerable population.” Its growing population faces poverty, food insecurity and instability. This can lead to mass migration, which can further destabilize areas. Competition over scarce water and grazing areas also leads to conflict.

Ungoverned spaces. Many of the countries, including Sudan, Chad, Niger and Mali, have vast territory far from capitals or large cities. In Sudan, the far-western region of Darfur has been a continuing scene of violence and instability. In Mali, the north has been an ongoing challenge to the government in the capital Bamako, which is about 1,500 kilometers from Kidal, 1,200 kilometers from Gao and about 1,000 kilometers from Timbuktu. French and Chadian forces had to liberate all three northern cities from extremists in 2013 during Operation Serval.

Dissatisfied groups. Some distant regions in the nations along the arc are home to ethnic groups that consider themselves neglected by the central government. An example is the Tuaregs, Berber people who are nomadic, pastoralist and spread across several Sahel and North African nations. Their rebellion in northern Mali in early 2012 was the latest of many clashes with the central government.

External actors. Ungoverned spaces leave room for outside forces such as smugglers, drug runners and extremist groups to move freely. South American drug shipments frequently land in West Africa and are ferried through the Sahel and North Africa on their way to Europe. Sometimes illicit goods travel along ancient caravan routes in the Sahel and Sahara regions.

Rudolph Atallah, a senior fellow at the think tank Atlantic Council, told ADF that landlocked countries in the arc such as Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger, Chad, South Sudan and Ethiopia have to rely on neighbors’ seaports for goods and support. If a problem emerges in one country, it easily can become a problem in several more.

“When Côte d’Ivoire had a coup in 2002, it split the country down the middle,” Atallah said. “The food supplies and other supplies that were actually making their way up into those landlocked countries of Burkina [Faso], Mali, Niger … they slowed down to a trickle. And it took several years for that to shift over to Ghana.” Such conditions can exacerbate existing poverty. At the same time, organized crime increased in the region as illicit trades grew in these landlocked countries.

In the midst of this, Atallah said, shifting population demographics and severe poverty have pushed people toward new ideologies. Various terrorist and extremist groups thrive in areas where government aid and institutions are at their weakest. “So this is an area where people are disgruntled, local economies have been extremely weak, they haven’t been able to reach those people that are marginalized,” he said. “And many of them are just trying to take matters into their own hands.”

Many conflicts have arisen along and near the arc over the years. Civil wars have beset Sierra Leone, Liberia and Côte d’Ivoire south of the arc. Chad has had numerous coups. Somalia has been in disarray since the early 1990s. Sudan and South Sudan have been at odds. Libyan dictator Moammar Gadhafi fell. Many of the weapons from Libya flowed out of the country and into the hands of other groups. Many of those groups are present in Mali, an active hot spot along the arc.

THE CHALLENGE OF MALI

Mali offers a textbook example of how these diverse forces can come together to create instability. Exhibiting characteristics common to many countries in the arc, Mali has limited arable land and resources, a vast and sparsely populated north, disaffected ethnic groups, and external actors in the form of al-Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) extremists, traffickers and former loyalists to Gadhafi.

The volatile mixture exploded into conflict in 2012. Tuaregs, who live in the nation’s northern desert, rebelled after years of dissatisfaction with the government. In January 2012, the Tuaregs attacked northern towns, which led to residents fleeing into Mauritania, according to a BBC timeline. In March 2012, the Malian army overthrew President Amadou Toumani Touré, accusing him of failing to respond effectively to the Tuareg rebellion. By April, Tuaregs had taken control of the north and declared independence.

The presence of groups such as Ansar al-Dine, an Islamist rebel group that translates as “defenders of the faith,” and AQIM shows how easily outside groups can move about in ungoverned spaces. Also present in Mali is the Movement for Oneness and Jihad in West Africa (MUJAO), which merged with terrorist Mokhtar Belmokhtar’s Masked Men Brigade, according to the BBC. Belmokhtar is accused of executing a deadly siege at an Algerian gas plant in January 2013. MUJAO, an AQIM splinter group, historically has been most interested in profiting from criminal activity in the region, according to the Civil-Military Fusion Centre.

In January 2013, French forces launched Operation Serval, entering the country to reclaim northern territory taken by insurgents. In the spring, French forces gave way to troops sent in by the Economic Community of West African States, an operation called the African-led International Support Mission in Mali. Now the United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA) is patrolling the nation and trying to maintain order in this fragile setting.

NO EASY SOLUTIONS

Having diverse nations in different regions, each with unique challenges, makes an overall solution to the arc of instability virtually impossible. Monetary aid to these countries is essential, Atallah said, but it must be accompanied by oversight and accountability. That rarely happens. Addressing poverty, ensuring strong, ethical government — all are also crucial to preserving stability. But what can militaries and security forces do of their own accord to help ensure stability across the arc? That question has no easy answer.

Dr. Dona J. Stewart, senior fellow at Joint Special Operations University, told ADF that ultimately, military activities in unstable areas have to be linked to political, economic and development goals. That requires extensive planning. It’s certainly outside the control of Soldiers and security forces.

“One of the major roles for militaries is providing the security to allow other forms of development — political, economic, educational, health — to take place,” Stewart said. “You can’t have those types of development unless you have security.”

This is achieved best when security is “carefully calibrated” with political goals in a place like Mali, where tensions between the north and south are entrenched, Stewart said. Individual commanders and Soldiers can achieve this delicate balance by doing several things.

This is achieved best when security is “carefully calibrated” with political goals in a place like Mali, where tensions between the north and south are entrenched, Stewart said. Individual commanders and Soldiers can achieve this delicate balance by doing several things.

“First of all, they need to have a good understanding of the social-cultural context in which they’re operating,” Stewart said. This is especially important in a place like Mali. Malian Soldiers from the south should be sensitive to and knowledgeable of the cultures of the vast north. The 12,640-person MINUSMA mission comprises 35 nations from Africa, Asia, Europe and North America, magnifying the need for cultural sensitivity.

Discipline also is crucial, and it goes hand in hand with cultural concerns. The two principles can empower Soldiers to “judiciously apply force when needed, but also have the skill set to find solutions to problems that may not necessarily need force,” Stewart said. Examples could include working with humanitarian aid agencies or addressing infrastructure problems.

Success also can depend on how forces view counterterrorism. Stewart said the past decade has seen counterterrorism as “specific kinetic activity against specific targets.” That tactic can be open-ended.

“Our understanding has increased to realize that the indirect types of activities are absolutely crucial for developing any sort of outcome that’s going to be enduring and lasting,” she said. “And for this arc in particular, it’s going to be indirect types of activities that are going to be really necessary to develop.”