After Five Years, France’s Operation Barkhane Sees Progress Toward Peace in the Sahel

ADF STAFF | Photos By Reuters

Operation Serval marked a high point for France’s military in the modern era. The 18-month mission began in January 2013 at the request of Mali’s government as extremist groups pushed south and threatened to overrun the capital, Bamako.

The 4,000-person French effort used a combination of ground forces, aerial bombardments, armored divisions and special operators to halt the advance, liberate all major cities in Mali’s north, and decimate the extremist leadership. Three of the five top terror leaders in Mali were killed, and two others –– Mokhtar Belmokhtar and Iyad Ag Ghaly –– fled Mali.

When then-President Francois Hollande visited liberated areas, he was met by adoring crowds. Children climbed walls to fly the French tricolor, and elderly people threw their arms around French Soldiers. In cities such as Menaka, Timbuktu and Gao, Malians had suffered greatly during the brief extremist occupation and were grateful for a fresh start.

“It was a total panic before; we didn’t sleep. We were not free to do what we wanted, but today we feel total liberty,” a man in Timbuktu told France 24 television news in January 2013.

“It was a total panic before; we didn’t sleep. We were not free to do what we wanted, but today we feel total liberty,” a man in Timbuktu told France 24 television news in January 2013.

But the feelings of exhilaration quickly gave way to the difficult task of preserving the peace. Remnants of extremist groups retreated to rocky formations in the far north nicknamed Planet Mars, forcing French forces and their allies to conduct a painstaking search-and-clear mission. Members of the Tuareg ethnic group signed a tenuous peace deal. The Malian Army remained divided with rumblings of a coup. In early 2013, suicide bombers struck Kidal and Gao, signaling that extremists had not given up.

The French knew the remaining mission would be more difficult. It meant crossing borders, working with regional partners and the United Nations, training local forces, and fighting alongside them to wipe out terrorist enclaves. On August 1, 2014, France launched Operation Barkhane. The mission was simple: Finish the job.

With Operation Serval “we prevented the creation of what you might call a ‘Sahelistan,’ ” Gen. Patrick Bréthous, then commander of Barkhane, told Radio France Internationale. “The situation is stabilized in Mali. There is a peace accord signed and put in place. But there remain insurgents, and it’s against these last ones that we now fight.”

Scope/Strategy

Operation Barkhane is the military component of France’s three-pronged Sahelian strategy. Other aspects are supporting economic development and pursuing political engagement.

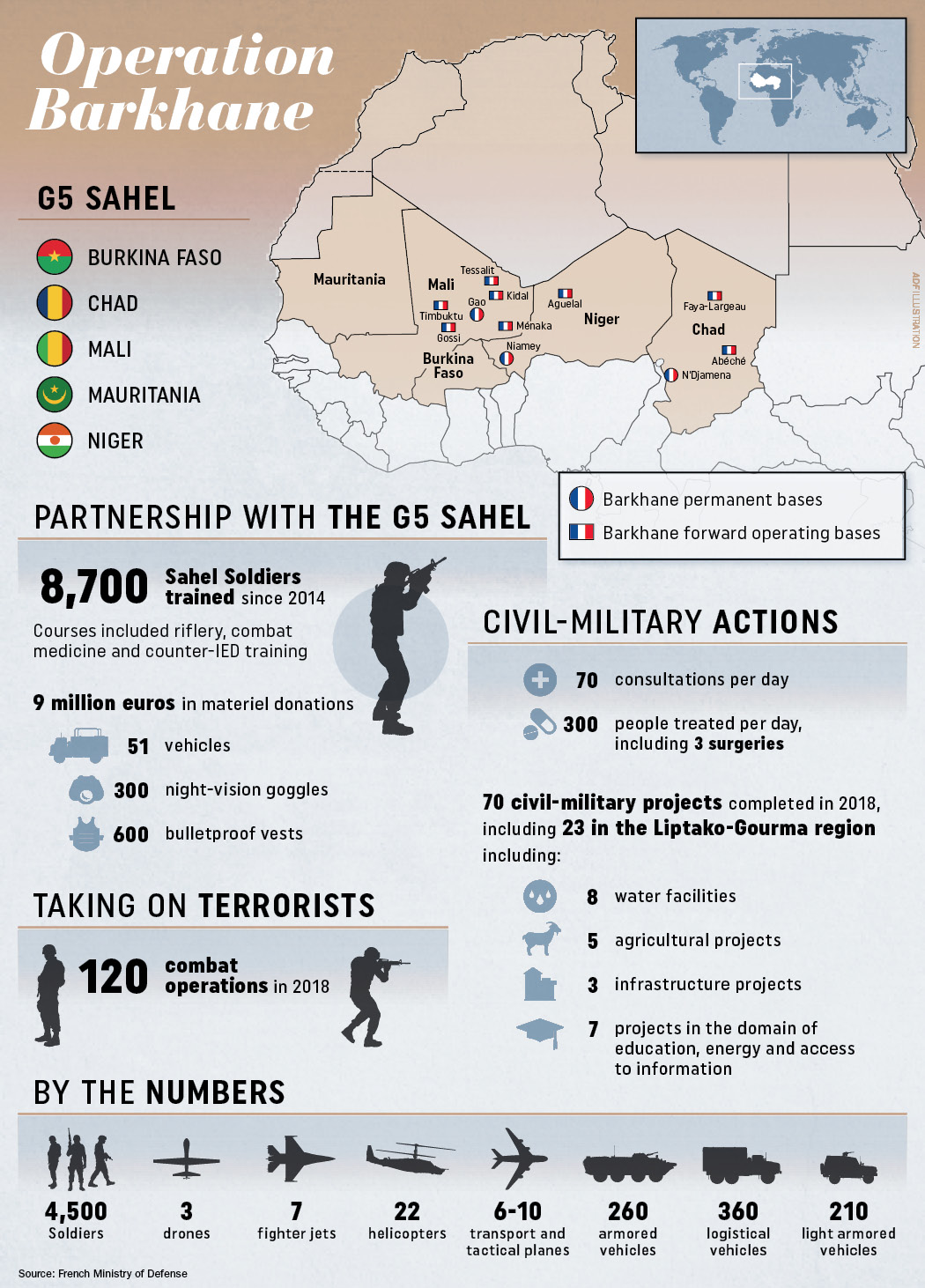

There are three permanent bases that support the mission: in Gao, Mali; Niamey, Niger; and N’Djamena, Chad. Additionally, in isolated zones, Soldiers set up plateformes desert-relais, or forward operating bases. With 4,500 Soldiers deployed, Barkhane is the largest French military effort in the world.

Ground

The majority of the operation’s infantry troops are based in Mali, where about 2,650 Soldiers specializing in desert tactical warfare are divided between the main base in Gao and forward bases in Gossi, Kidal, Menaka, Tessalit and Timbuktu.

Barkhane places a particular emphasis on the Liptako-Gourma region –– the border area where Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso meet. A 2019 study by the Africa Center for Strategic Studies found that 90% of Islamic State attacks in the region are within 100 kilometers of the three countries’ borders.

The Barkhane presence has helped reopen commercial routes and provided the security necessary for the return of civil administration in many tri-border towns. In 2019, Liptako got its first governor since the 2013 crisis. Barkhane also has helped the Malian Armed Forces establish three bases in the border area. The U.N., Barkhane, the Malian Army, Malian police and gendarmes share a unique joint base in Menaka.

“These border areas are obviously the most sought-after places by terrorists to carry out their actions,” said Gen. Frederic Blachon, Barkhane force commander. “There is no better way to move from one to the other and find refuge than in a border area. So the Gourma region for us presents all the conditions necessary to be effective.”

Air

Barkhane’s military aircraft are mostly at airfields in Niamey and N’Djamena. The fleet includes transport and combat jets. There are seven Mirage 2000 jets nicknamed the “eyes in the sky.”

“These platforms play a major role at the heart of the operation,” the French Ministry of Defense said in a statement. “The presence of transport planes and aerial resupply planes allows us to elongate the theater of operations and rapidly move to any part of the Saharo-Sahelian Band. The presence of combat planes and drones allows us to permanently threaten our adversaries and hit them when necessary.”

The mission uses three CH-47 Chinook transport helicopters provided by the United Kingdom’s Royal Air Force and 16 combat helicopters. In 2019, Denmark announced its plan to donate two Merlin transport helicopters to the mission. Barkhane also flies three MQ-9 Reaper drones for reconnaissance and surveillance of targets, and feeds images in real time to deployed units.

An example of the airpower was in February 2019 when, at the request of the Chadian government, French Mirage fighter jets struck a column of 40 pickup trucks operated by a rebel group entering Chad from Libya. In other missions, jets will strike a terror enclave before ground troops enter to clear the area.

Troops deployed on a mission have dedicated aerial support.

“The missions are very long, from four to more than six hours, so we require numerous refueling sessions in air,” said Lt. Wilfred, a Mirage pilot who, as is customary for French Soldiers serving abroad, is identified only by his first name. “It’s atypical hours. We could be taking off very late at night or very early in the morning. Whenever an alert is triggered.”

The operational environment across the Sahel and particularly in northern Mali is daunting. Temperatures reach well above 40 degrees Celsius, sandstorms reduce visibility to almost nothing and, during the rainy season, many roads become impassable.

To maintain operational rhythm and allow units to stay in forward operating bases, Barkhane uses air and land transport. The mission uses three West African ports to import materiel. Truck convoys, which can grow to include 100 vehicles and require air support and armed escorts, move equipment to the front lines.

For example, a logistical convoy traveling 360 kilometers between Gao and Kidal consisted of 60 vehicles carrying 135 metric tons of cargo and 340 cubic meters of fuel. The convoy was supported by 10 escort vehicles, aerial surveillance, medical staff and two tow trucks.

“This logistic convoy requires a permanent readiness for many unexpected technical and security problems,” said Capt. Freddy, commander of the logistics unit. “My men are well-trained and have endurance, which allows them to anticipate and react effectively.”

The mission also relies heavily on aerial resupply drops to remote outposts. It has received logistical support from partners including Spain, which has flown a C-130 based in Senegal and a C-295 in Gabon to supply Barkhane.

‘Permanent Adaptation’

Not long after the creation of Barkhane, a terror group known as the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS) formed. It operated mainly in eastern Mali and neighboring regions of Niger and Burkina Faso.

In late 2016, the group made its presence felt with three significant attacks in Burkina Faso. The group attacked a gendarmerie, a police outpost and a prison, where it unsuccessfully tried to free jailed extremists. Three weeks after the third major attack, the Islamic State acknowledged the group, while not naming it an official Islamic State wilayat, or province.

At the same time, the region saw increasing intercommunal violence, particularly in Mali. In one horrific attack in the Mopti region of eastern Mali, nearly 160 people were killed in clashes between Fulani herders and Dogon hunters. Extremists have sought to exacerbate ethnic tensions as a recruiting tool.

The difficulty led one major French newspaper to ask whether Barkhane was “mission impossible,” pointing out that 4,500 Soldiers cannot reasonably control an expanse of 5 million square kilometers, an area 10 times the size of France. The year 2019 set a record as the deadliest on record for extremist violence in the Sahel.

The challenge has pressed Barkhane’s leadership to emphasize the quality of “permanent adaptation” in its planning.

Then-Commander Gen. Bruno Guibert said French forces have evolved to move faster and travel with a smaller footprint since the mission began. “We have to travel further, longer and as light as possible,” he told the French newspaper Liberation in 2018. “We are prioritizing operations long on the ground, bivouacking, often for a month or more. We are trying to reduce our logistical footprint to match the velocity of the enemy.”

There have been notable successes. In October 2019, French officials announced they had killed Ali Maychou, a Moroccan who led the Group to Support Islam and Muslims. He was the second-most-wanted terrorist in the Sahel at the time of his death. Patrols in the tri-border region have likewise decimated the leadership of ISGS.

Guibert said that Barkhane has improved its network of human intelligence, earning the trust of local civilians who can serve as its eyes and ears. He added that the mission is using biometric tools to identify terrorists.

“I don’t need more cannons; I have all that is needed to hit the target,” he said. “What I need are the tools adapted to contain the enemy who has mobility. … For a year we have considerably expanded our network of sources in the population, and that’s a good sign.”

Serving the Public

ADF STAFF

In many parts of the Sahel, civilians have been traumatized by years of conflict. Often they do not trust the armed forces that are supposed to protect them.

Recognizing this, Barkhane has made civil-military operations (CIMIC) a cornerstone of the mission. Nearly every operation has a civilian outreach component, which can include free health clinics and projects that provide access to water, energy or education.

In 2018, Barkhane forces conducted about 70 CIMIC projects. These included drilling wells in Menaka, Mali, renovating a milk farm in Menaka and building a bridge in Tassiga, Mali. In the first seven months of 2019, Barkhane had conducted 30 CIMIC projects, including 13 in the tri-border Liptako-Gourma region. Barkhane CIMIC teams also provide daily health care, treating an average of 300 people per day.

Larger ongoing projects will repair Menaka’s electric power station and support its police station with new vehicles and infrastructure improvements.

“It’s essential to evaluate the needs of the people, to give them the means to access water and primary care, to promote their working conditions and their living conditions,” said Maj. David, a CIMIC project leader based in Gao. “All of this contributes to improving the general security situation for the population.”

CIMIC teams are working hand in hand with their Malian counterparts to emphasize the importance of public engagement. Barkhane forces have provided training and launched a public relations campaign that includes posters highlighting the professionalism of the Malian Armed Forces.

A Malian CIMIC officer, Sergent-Chef Samba, patrolled Menaka in January 2019, stopping to talk with people and asking about their lives. He said that after a string of CIMIC events such as handing out back-to-school kits, he has noticed a change in the way people interact with him.

“Now we’ve acquired a certain notoriety,” Samba said. “People come to see me to share the problems they’re having, and we think about it together to decide what type of actions to put in place to address them.”

Training is ‘How We Will Win’

ADF STAFF

From the outset, France has stressed that Barkhane is not an indefinite mission. As soon as possible, it intends to give way to local forces. As often as possible, France wants to partner with national militaries, regional efforts like the G5 Sahel Joint Force and the United Nations.

Therefore, training and joint missions are a central part of Barkhane. In the first seven months of 2019, Barkhane conducted 308 training events or “combat accompaniments” with partner forces. During that same time, 3,000 Soldiers completed a training program, and 1,500 participated in a combat accompaniment.

Areas of emphasis included rifle training, demining, human rights law and battlefield medicine.

From April 15 to 17, 2019, in Timbuktu, French Marine Corps Infantry improvised explosive device experts trained Malian counterparts on how to identify explosives, defuse them and how to drive on a road studded with land mines. The exercise ended with a driving test in which Soldiers had to navigate a mined road.

“Thanks to this training, my men will be able, in turn, to train all of our sections and transmit these best practices,” said Capt. Samake, head of the Malian detachment. “It’s no secret. This is how we will win.”

Joint missions also are beginning to show success. In 2019, France held four events called DIDASKO in four Sahel countries. These events were designed to prepare troops for joint missions.

In December 2018, the presidents of France and Burkina Faso signed an agreement to pursue joint military action. The first major joint effort was from May 20, 2019, to June 3, 2019, when 450 Soldiers from Barkhane conducted a major operation with their Burkinabé counterparts near the Malian border region of Gourma.

After the mission, Col. Jean Francois Calvez of France’s Richelieu Desert Tactical Group had nothing but praise for his Burkinabé counterparts. He envisioned further partnerships.

“This was a very high-quality unit with combined capabilities, well-commanded with volunteer Soldiers who were quick to react and perfectly integrated in the mission,” he said.

Comments are closed.