Putting Principles Ahead of Power

Africa’s greatest leaders found a variety of ways to govern, including delegating authority and leading by example.

ADF STAFF

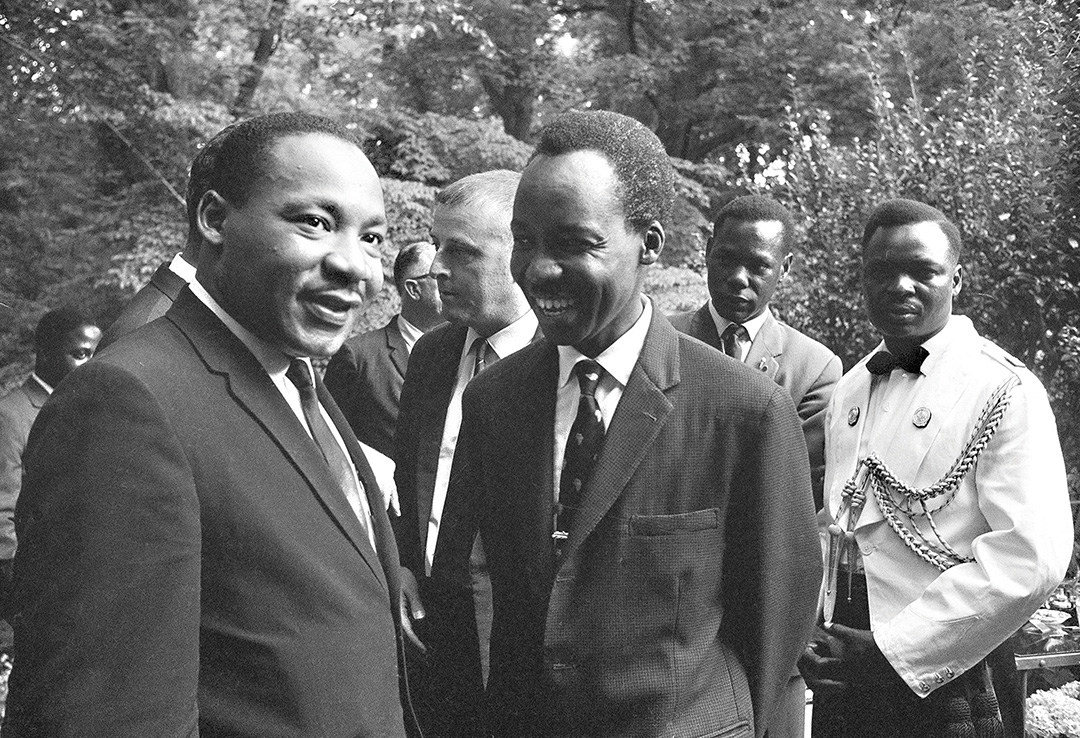

In his autobiography, Nelson Mandela recalled how he met the president of Tanzania in March, 1990.

“We arrived in Dar es Salaam … and I met Julius Nyerere, the newly independent country’s first president,” Mandela wrote in Long Walk to Freedom. “We talked at his house, which was not at all grand, and I recall that he drove himself in a simple car, a little Austin. This impressed me, for it suggested that he was a man of the people.”

That the two men would meet was inevitable. Mandela and Nyerere were among the most-admired leaders of their time, and they remain the gold standards for ethics and honor in leadership. It’s difficult to study the career of either man without finding the other man referenced.

“Their power of examples shows how ethical leaders navigated their nations through internal divisions to stability and how ethical norms became inculcated into the security services that they left behind,” wrote Paul Nantulya of the Africa Center for Strategic Studies.

Ethics in government is a challenge the world over. In March 2001, the African Leadership Council issued “The Mombasa Declaration,” a statement asserting the need for honorable, competent governments in Africa.

“We recognize that leadership, especially in Africa, is difficult,” said the declaration. “There are many challenges, particularly of political culture, poverty, illiteracy and disunity. Yet, we have come together in Mombasa to maximize and affirm the potential for positive leadership on our continent.”

The declaration noted the qualities of great leaders: “Positive leaders in Africa stand out because of their adherence to participatory democratic principles and their clear-minded strength of character. Transformational leaders improve the lives of their followers and make those followers proud of being part of a new vision. Good leaders produce results, whether in terms of enhanced standards of living, basic development indicators, abundant new sources of personal opportunity, enriched schooling, skilled medical care, freedom from crime, or strengthened infrastructures.”

MANDELA, LEADING FROM PRISON

Mandela spent 27 years in prison, and out of necessity developed a leadership style that relied on individual initiative and shared ethical values. As the leader of a movement whose followers were, in many instances, either incarcerated themselves or in exile, Mandela had to delegate authority and lead through persuasion, rather than fiery rhetoric. His followers had to be decisive, rather than wait for central direction. They developed as independent thinkers. Nantulya said that Mandela developed a culture of “collective leadership” and “shared ethics” that his followers adopted.

“This approach carried over to when Mandela entered office as president, according to his successor, Thabo Mbeki,” wrote Nantulya in a study, “Africa’s Strategic Future: The Consequence of Ethical Leadership.” “While setting forth broad principles, he left the day-to-day leadership and implementation to younger colleagues. In the process, he helped create a culture of leadership rejuvenation and initiative.”

Mbeki said that Mandela and his followers had to lead by example. “At all times they understood the need to inspire confidence among those of us who were following them by paying very close attention to the manner in which they conducted themselves in private and in public.”

Mandela knew that his example was a full-time job. After his release from prison, he began meeting with leaders throughout Africa and wrote that he was regarded with suspicion.

“I knew that over the previous few years some of the men who had been released had gone to Lusaka and whispered, ‘(Mandela) has become soft. He has been bought off by the authorities. He is wearing three-piece suits, drinking wine, and eating fine food.’ I knew of these whispers, and I intended to refute them. I knew that the best way to disprove them was simply to be direct and honest about everything that I had done.”

When Mandela was elected South Africa’s first black president, he announced that he would serve only one term, although two were allowed.

In their book, Winning the Long Game: How Strategic Leaders Shape the Future,” authors Paul J.H. Schoemaker and Steven Krupp said that Mandela was a master of adaptation.

“Mandela exemplifies how a strategic leader adjusts strategy and execution amid complex social, political, legal and economic forces without compromising deeply held values,” they wrote. “Leadership is not just about motivating people and creating political support for a strategy, but also about maintaining broad support through successive adjustments to the plan.”

NYERE, THE MWALIMU

The Swahili word mwalimu means “teacher,” but in Tanzania, is it also the nickname for Nyerere, the country’s founding president. Nyerere believed in the African concept of Ujamaa, meaning “brotherhood.” In a 2017 study, Nantulya said Nyerere was guided by the principles of “servant leadership.” Servant leaders practice “honesty, accountability, good stewardship of public resources, accessibility to the public and open government.”

Nyerere’s approach to leadership was grounded in the influences of being a member of a tribe as a child, and the emphasis on tribal consensus. He was also grounded in the ideals of Christianity, which he had learned in school.

His country gained its independence without war, a tribute to Nyerere’s integrity, his skill as persuasive orator, his considerable abilities as an organizer, and his ability to work with different groups, including British colonialists.

Nyerere became an international figure, gaining “prestige for his principled support of the struggles for majority rule in South Africa, Namibia, Zimbabwe, Mozambique and Angola,” reported The New York Times. He also ordered a military counteroffensive against Idi Amin of Uganda, which routed the dictator and sent him into exile.

Under Nyerere, the values of Ujamaa were taught to all levels of the armed forces. “This extended to the national youth services that provided a wide pool of potential recruits, as well as the Kivukoni Academy for senior civilian and military leaders,” wrote Nantulya. “As a rule, civilian and military members trained together from the junior to senior level, creating healthy civil-military relations in the long term.”

When Nyerere became president, Tanzania was one of Africa’s poorest countries. Nyerere believed that socialism would cure his country’s poverty. Under his leadership, Tanzania made great advances in health and education. But economically, socialism was an experiment that ultimately failed.

Nyerere stepped down as president in 1985 after 24 years. He was the third African leader to give up power voluntarily in the modern era, and he retired to a farm in his home village near Lake Victoria.

Nyerere remains revered throughout Tanzania as a man of principle who would not tolerate even the appearance of privilege. His leadership style has been described as leading by the power of example and the strategic use of state institutions.

RAMGOOLAM and KHAMA

Robert I. Rotberg, who directed the establishment of the Index for African Governance, has said that Seretse Khama, Botswana’s founding president, and Seewoosagur Ramgoolam, Mauritius’ first leader, are examples of honest, capable governance.

Khama was president from 1966 to 1980 and is remembered for laying the foundation for ethical and open government in the young democracy. “Modest, unostentatious as a leader, and a genuine believer in popular rule, Khama forged a participatory and law-respecting political culture that has endured under his successors,” Rotberg wrote in 2005.

Khama’s legacy continues. The research group Transparency International says that Botswana has the best perceived corruption ranking in Africa — and has for 20 years. The country has a record of uninterrupted democratic elections. The country has elected three presidents since Khama, with his son Ian serving 10 years before stepping down in March 2018.

Ramgoolam was the prime minister of Mauritius from 1968 until 1982. He largely shaped his country’s government and foreign policies. As prime minister, he established free universal education and free health care, along with introducing pensions for the aged. Although his later years as governor were not entirely successful — the economy stagnated for a time — today he is regarded as “Father of the Nation.” His son Navis has served three terms as the country’s prime minister.

Ramgoolam, said Rotberg, “gave Mauritius a robust democratic beginning, which has been sustained by a series of wise successors from different backgrounds and parties.” Today, Mauritius has the highest ranking on the Human Development Index — a composite statistic of life expectancy, education, and income — of any country in Africa.

Khama and Ramgoolam were in positions as leaders to establish strong, single-man, kleptocratic regimes — “But they refused to do so,” Rotberg said.

THE PRESIDENT WHO LEFT

A painful issue facing many African countries is leaders who refuse to leave office. They change their country’s constitutions to allow for more than two terms, they meddle in the elections, and they refuse to accept election results when they lose. Some are afraid to leave office, knowing that their successors might find evidence of corruption.

A report by the Africa Center for Strategic Studies found that countries that enforce term limits on leaders are less prone to armed conflict than those where leaders stay indefinitely.

Patrick Magero, a lecturer at the United States International University Africa in Kenya, calls it a “third time problem.”

“The role of retired presidents in society has never been clear, which makes it difficult for most leaders to let go of power,” he said, “but the culture of respecting term limits is gaining a foothold across the continent.”

Joaquim Chissano respected term limits. He was the second president of Mozambique, serving from 1986 to 2005. When he took office, his country was in the throes of a civil war that began in 1977. He initiated sweeping changes, including changing the economic model from socialism to capitalism. In 1990, his country passed a new constitution that helped establish a multiparty political system and free elections. He began peace talks with the rebels, and the civil war ended in 1992.

In 2001, the popular Chissano announced that he would not run again for president — a move that was seen as critical of such leaders as Robert Mugabe, who was then serving his fourth term as president of Zimbabwe.

On Chissano’s 68th birthday in 2007, the Mo Ibrahim Foundation awarded him its first Achievement in African Leadership award. It consists of an initial $5 million gift, plus $200,000 a year for life. It recognizes African leaders “who have developed their countries, lifted people out of poverty, and paved the way for sustainable and equitable prosperity.” The award also “ensures that Africa continues to benefit from the experience and expertise of exceptional leaders when they leave national office, by enabling them to continue in other public roles on the continent.”

The award’s judges said that “Mr. Chissano’s decision not to seek a third presidential term reinforced Mozambique’s democratic maturity and demonstrated that institutions and the democratic process were more important than the person.”

Since the award was established in 2006, it has been given only five times.

The Code of African Leadership

In 2004, the African Leadership Council introduced its Code of African Leadership. The council asked the African Union and the heads of Africa’s nations to adopt the code, and reject the “unfortunate” examples of bad African leaders including Idi Amin, Jean-Bedel Bokassa and Mobutu Sese Seko.

The code says that African leaders serve their people and nations best when:

- They offer a coherent vision of individual growth and national advancement with justice and dignity for all.

- They seek to be transformational more than transactional leaders.

- They encourage broad participation of all levels of society, including all minorities and majorities, and emphasize the deliberative nature of the best democratic practices.

- They demonstrate in their professional and personal lives deep respect for the letter and the spirit of all of the provisions of the national constitution, including strictly abiding by term limits.

- They lead by example and teaching to acquaint their peoples with respect for dissent, the ideas of others, and the importance of disagreement between political parties and individuals.

- They enforce rulings of all courts and independent tribunals and emphasize and strengthen the independence of the judiciary, so as to bolster the rule of law.

- They respect international conventions and international laws.

- They promote transparency and encourage and adhere to internationally common forms of accountability.

- They recognize that they are accountable for their actions and that no one is above the law nationally and internationally.

- They accept peer review.

- They promote policies aimed at eradicating poverty and enhancing the welfare and livelihood of their people within an appropriate macroeconomic framework.

- They strengthen and improve access to education and health care.

- They respect all human rights and civil liberties.

- They demand and work for the peaceful and lawful transfer of power.

- They promote and respect the separation of powers by ensuring financial autonomy of the judiciary and parliament, and ensure that the judiciary and parliament are free from unlawful interference by the executive.

- They adhere to a strong code of ethics and demand the same from all subordinate officials and cabinet ministers.

- They do not use their office for personal gain and avoid (or declare) all conflicts of interest; they declare their personal and immediate family assets yearly.

- They specifically eschew corrupt practices and expose those in their official capacities that violate national laws and practices against corruption.

- They ensure human security.

- They respect freedom of religion.

- They respect freedom of the press and media.

- They respect freedom of assembly.

- They respect freedom of expression.

Comments are closed.